In those few seconds at the end of the runway when the pilot pushes forward on the throttle levers and the engines quickly change from idle to something approaching full thrust, the feeling can be incredibly thrilling if you let your soul off the leash a little instead of distracting it with a book, a sweet or a little conversation.

When I’m far away from any planes or airports, I occasionally wonder whether those few seconds are the closest a person can comfortably get to death without actually dying. That strange sensation of putting your body through a dangerous situation that it’s not really meant to be subject to can do peculiar things to you. So much could go wrong when you’re on a plane, resulting in utter catastrophe, even though the probabilistic likelihood of anything actually going wrong is overwhelmingly slim.

In many ways this is a silly line of enquiry. Is flying any closer to death than standing on the edge of a cliff, driving a car down the motorway or even chopping onions? Probably not. But I imagine those few seconds at the end of the runway can still make you feel some horrendous things if you happen to have a propensity to be scared of flying.

Thankfully I’ve never been afraid of flying. That’s not to say I’ve never had some wild thoughts in those few pre-take-off seconds though. In the past, while letting my mind wander a little, thoughts of death have indeed raced towards me like a roman chariot as the pilot completes his final checklist.

So I was curious about how I would feel when flying for a trip to France recently, as this would be my first time on a plane since I started practicing meditation. Having seen my anxiety generally reduce in all aspects of life and my mind begin to quieten thanks to a daily meditation routine; the scientist within me was excited to see how my experience of travelling at 500mph in an aluminium tube would change with a slightly quieter and generally less-anxious mind.

I found that the answer was pretty much what I had anticipated; there were absolutely no irrational thoughts, no uncomfortable visions about death or crashing, I was left with a thrilling excitement underlying the experience, a joy at rising to greater heights on a pair of wings, through the clouds and up like an angel into the stratosphere.

The majesty of rising up to thirty-odd thousand feet, seemingly floating on nothingness is quite something. It feels like we’re not supposed to be there, like we’re breaking some unwritten law of nature, a transgression that will eventually have to be repaid in some Promethean enactment of justice.

Flying is crazy and beautiful at the exact same time; a bit like most things when you think about it.

France is full of mysterious wonders, passed down as gifts to us from those who lived in an earlier time. One such wonder lies near to Dol-de-Bretagne, in the Brittany countryside.

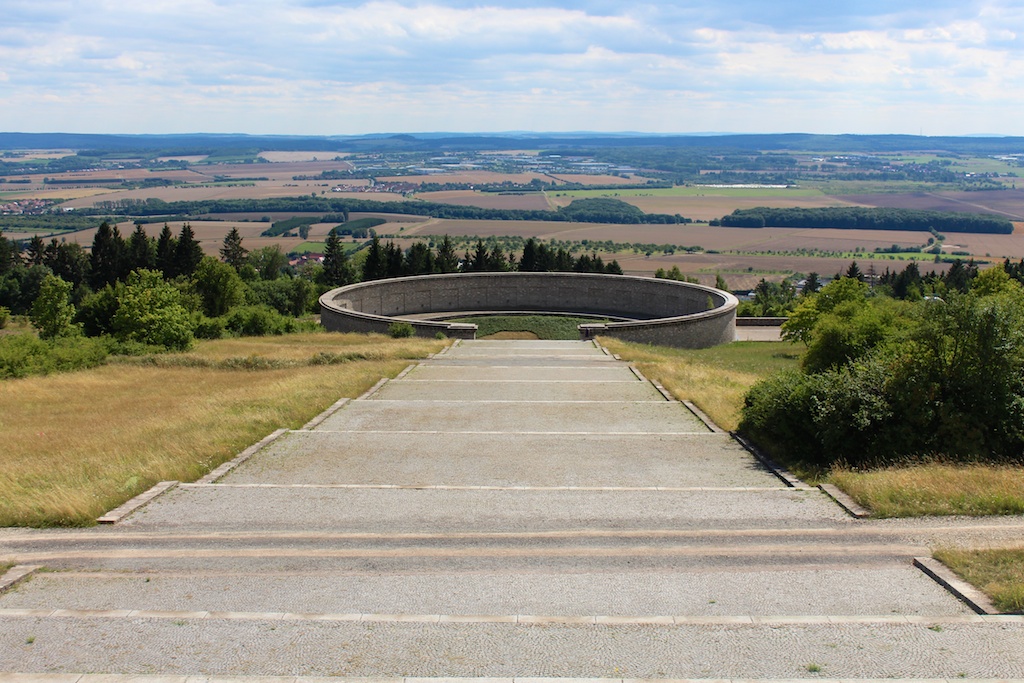

On the very edge of the town, in the middle of a farmer’s field, is a 120 tonne slab of granite over nine metres long that has, at some point, been dragged for miles to the top of a hill and raised so that it is rising up out of the ground at ninety degrees. We don’t really know who did it or why they went to such effort but our best archaeologists estimate it was erected in the neolithic period, probably around the same time as Stonehenge, around five thousand years ago.

The stone has been smoothly rounded at the end so that it points upwards towards the heavens, much like the steeple of a church. Although knowledge of its practical use has long since dissipated, the stone still stands firm after millennia as a beautifully subtle reminder that we should keep our eyes directed upwards, towards the sky, instead of downwards to our feet.

A few miles away in the very centre of Dol-de-Bretagne lies a cathedral. Unusually large for a Breton town so small, the cathedral was constructed in the 13th century.

Due to various bouts of destruction in the centuries since, it’s a bit of a hodgepodge of different architectural styles, but inside, as you walk through the front doors, you are confronted with a long narrow church that is overwhelmingly Gothic: it’s narrow nave rising high above your head, in a way that makes you feel as though your soul is being squeezed upwards into the heavens. It’s a peculiar feeling, but once you notice it, it becomes undeniable; as if an unconscious, ever-present force is willing you to rise up towards the sky.

The great Gothic cathedrals of Europe are undoubtedly one of the high points of human civilisation. Thankfully we are still graced with the existence of most of them, almost a millennium after their construction, for they truly are wondrous in every sense.

Dol-de-Bretagne is about four miles from the beautiful Brittany coast, lush in its tranquil coves and seaside towns surrounded by relatively untouched countryside, it’s not too dissimilar to that of Cornwall.

Driving away from the town, parallel to the coast, you can see the mighty wonder of Mont-Saint-Michel, steadfast and rising up out of nothing to emerge standing tall on a flat horizon.

A beautiful Norman abbey close to a thousand years old sits at the summit of Mont-Saint-Michel, a small rocky outcrop in the middle of a huge flat tidal bay. There is evidence to suggest the history of Mont-Saint-Michel stretches back at least two thousand years, with many interweaving layers of architecture and culture built up over the centuries. Some even say the island was once attached to the mainland and surrounded by a dense forest as recently as 1,500 years ago.

Due to the flat and desolate nature of the bay, the crowning abbey and its sharp spire can be seen from all directions upto twenty miles away; a majestic beacon forever pointing towards the sky.

The first time you see it, Mont-Saint-Michel has an amazing effect on you, there are few things in the world quite as distinctive. But it doesn’t lose its magic as the years roll by and you see it again and again, especially when viewed from the motorway when it’s raw wonder can be seen contrasted with the urban mundanity of twenty-first century life.

When driving around Northern France, the change of the landscape, as you move from Brittany into Normandy, is quite distinctive. The lanes of Normandy have a distinctive look due to something called bocage; the hedgerows either side of many country lanes rise high upon steep banks either side of the road, making it difficult to see into the fields beyond.

This unusual topographical feature made it notoriously difficult for Allied troops and armour during the Battle of Normandy towards the end of WWII, allowing the defending German forces to ambush the advancing armies with ease.

Today however, as I travel down the winding lanes of Normandy, overt traces of the fighting that took place in those same lanes three quarters of a century earlier have almost completely disappeared. Instead, the steep bocage banks lining so many lanes encourage you to look up towards the sky as your sight-lines across the neighbouring fields have been obscured. This experience is akin to that inside of a gothic cathedral; that feeling of your soul being squeezed upwards, willed to new heights by the natural cathedral of steep earthy bocage.

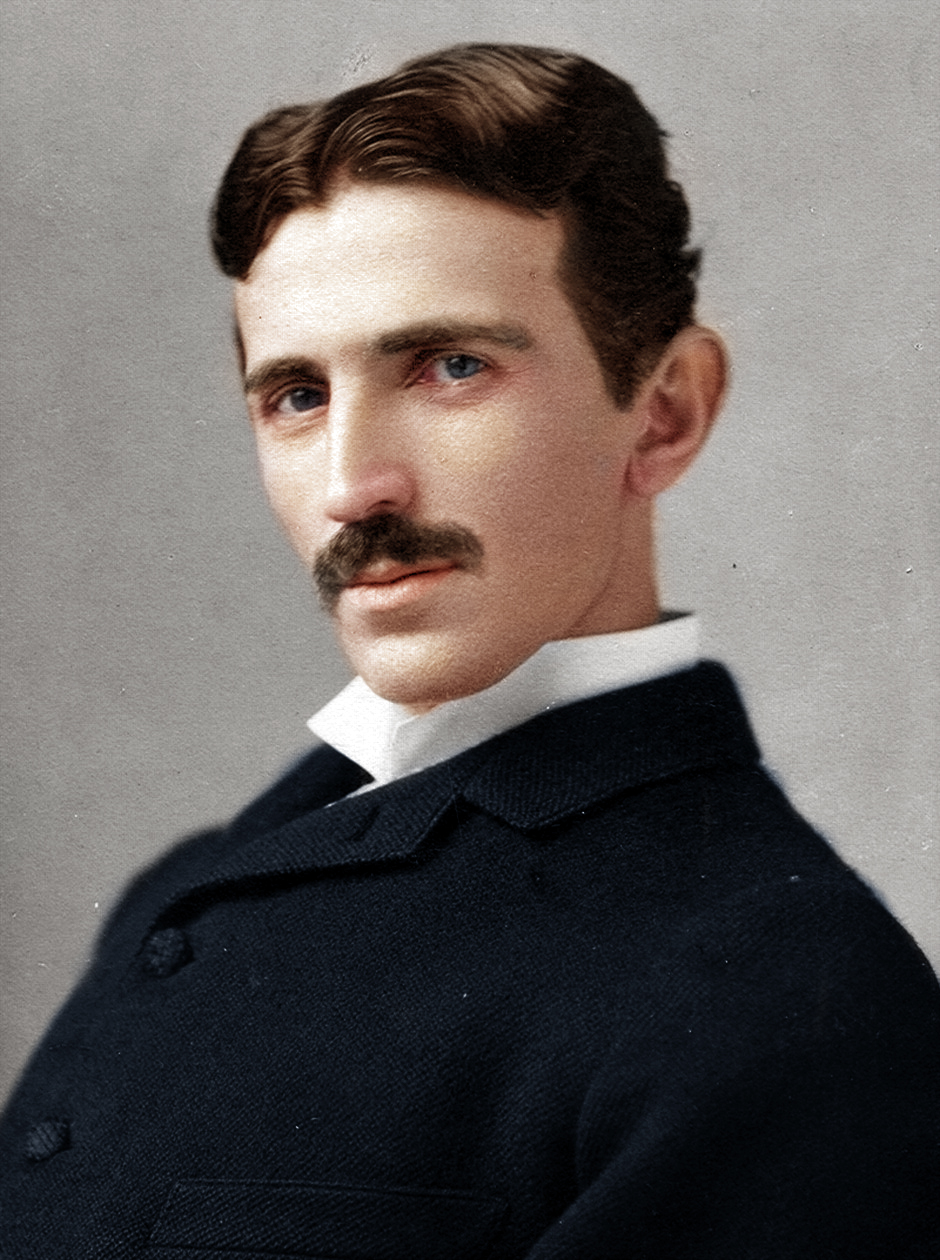

Halfway into my time in France, I sat reading Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, its timeless wisdom travelling down the millennia to blow my mind in the year 2019.

There are many things that are incredible about the book, not least of all its provenance which can be traced back to its careful preservation by a single man, Arethas of Caesarea, a Greek bishop in the 10th century who liked to collect manuscripts. He described his copy of Meditations as “so old indeed that it is altogether falling to pieces” and it’s only thanks to the dedication of that one careful soul that we can today read Marcus Aurelius’ literary and philosophic masterpiece.

But as I sat there in the Normandy sunshine leafing through the pages with the transcendent Move On Up by Curtis Mayfield gently playing in the background, I was suddenly struck by the books gentleness; the way that Aurelius wanted to communicate all of the beautiful, useful, subtle, ever-so-positive wisdom that he had accrued and filtered and distilled and shaped during the years that he was emperor of the largest empire to ever rule the world.

Apparently, Meditations is more of a personal diary than a book, Aurelius writing to aid his own personal development and never intending anybody else to read it. We’ll never know his true intentions, but to me, the book’s ninety pages are so incredibly well formed and calmly authoritative that it’s hard to imagine them not being written with other readers in mind.

Almost every sentence within the book’s pages is written, not on a journalistic whim or a stream-of consciousness burst but in a well-thought-through and meticulously edited collection of concise wisdom that gently reminds the reader how to go about transcending their current state and become a better, braver, more virtuous, more conscientious, more tolerant person.

The beaches along the western coast of Normandy between Avranches and Granville are surprisingly beautiful. They don’t have the quaint cosyness that the best Cornish beaches possess, mainly due to their vast length, but the sand is fine and golden, and they rarely get super busy.

After spending an excruciatingly hot few hours at a beach near the little village of Carolles, the drive back across the coastal hilltops provided a stunning view across the bay, and right in the middle of that vast tidal bay was the mighty Mont-Saint-Michel imposing itself yet again. Sometimes it feels as though it haunts my experiences like an immovable spectre, reminding us of our timeless connection to those who came before.

I recently read how, in early August 1944, Ernest Hemingway dragged most of the US press corps who were in Normandy reporting on the invasion of Europe (including Robert Capa and Charles Collingwood) to Mont-Saint-Michel for a huge party lasting days, drinking copious amounts of vintage wine given to them by the proprietors of the famous Hôtel de la Mère Poularde after being kept hidden from the occupying Germans for years in a secret cellar.

Ernest Hemingway, Robert Capa and Charles Collingwood along with all of their memories, experiences and stories are now long gone from this Earth, but Mont-Saint-Michel remains; standing firm against the relentless barrage of waves that ever-so-slowly wear away its rocky surface.

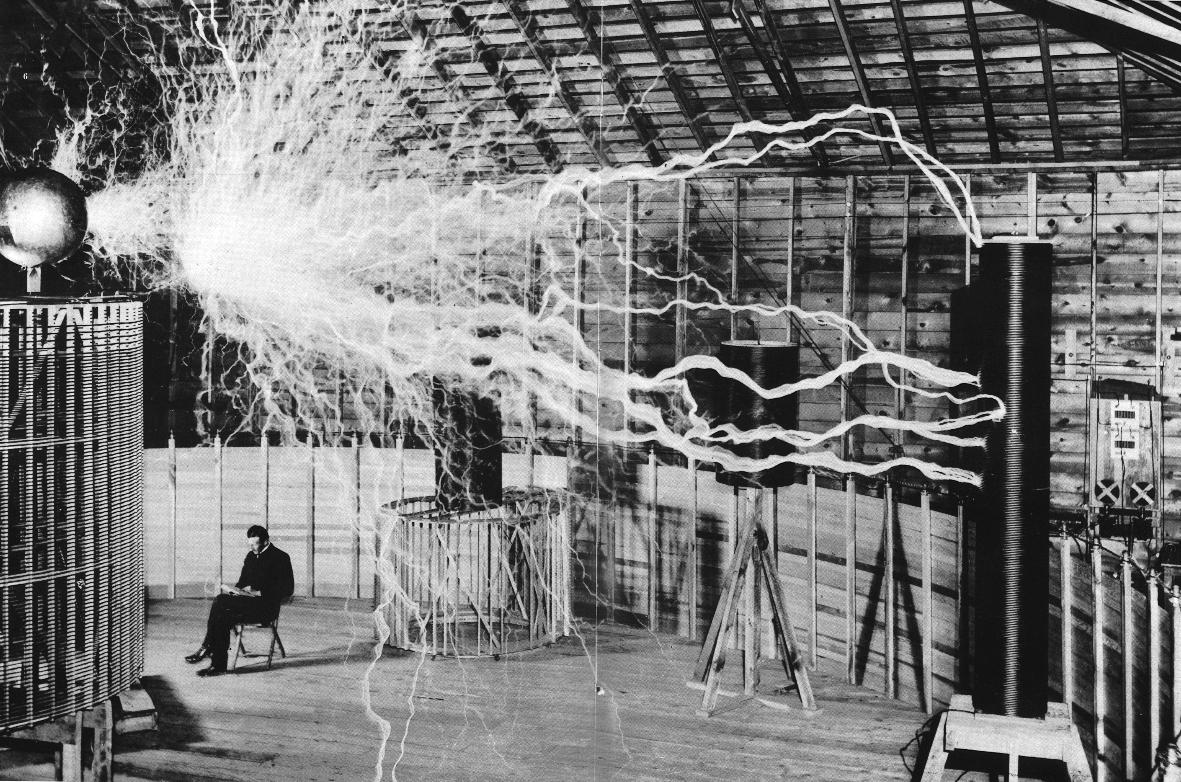

On another day, a journey through the Normandy countryside bought me to an old dam, built in 1932 to generate hydroelectricity.

It once held back the Selúne river to create a huge new lake, but now, with the dam’s sluice gates permanently open and the lake completely gone, it’s in the process of being demolished.

There is no doubt that dams are true marvels of engineering. It’s no less of an incredible feat that a beaver is able to build a structure out of wood that can hold back the force of a raging torrent than it is that our species figured out how to hold back the Colorado and the Yangtze. They say that so much concrete was used in the construction of the worlds largest dams, they will be one of the last large vestiges of human civilisation remaining after our species has long faded into extinction.

But ultimately, how wise is it to hold back the forces of nature?

A dam can generate energy, it can protect us from danger, but preventing natural forces from flowing is bound to eventually lead to major problems elsewhere.

The dismantling of the dam on the Selúne in Normandy has resulted in years of protests from locals who had grown accustomed to the way things have been for the last few decades, drawing a sense of safety and comfort from the holding back of nature.

But maybe sometimes, it’s better to just let things flow instead.

As my time in France reached an end, I was left thinking about Marcus Aurelius and his gentle message of transcendence. Like the Gothic cathedrals and so many of the things I saw while I was in France; rise up, he wills us. Because we all have the opportunity, if we choose to grasp it, to transcend and be better than we were yesterday.