A Rumination on Adam McKay’s Vice

”Beware of the quiet man. For while others speak, he watches. And while others act, he plans. And when they finally rest……he strikes.” – Anon

It feels like the world is becoming more complex.

So what’s causing this new complexity?

Well, there do seem to be more ideas floating around today. Everyone’s mind is working overtime churning out opinions and thoughts, and with more people in the world now than at any time in history, it’s enticing to adopt the logic that all those new thoughts (in the form of Tweets, articles, books, interviews and conversations) are making society more complex. But maybe most of these ideas and opinions are simply recycled, reused and remixed from older ones? Indeed, originality is a hard concept to pin down, but it seems to me that little of what flows out of us today can be labelled truly original.

So what about technology? It does feel like all the new technology that we are inventing is producing more complexity in society, for sure. But crucially, I feel our technological inventions of the past century have led to a new and radically different way of seeing the world; one where the things in the natural world begin to look and feel like the technology we are inventing.

Once we begin interacting with computers more than people; everything in reality starts to feel like it is constructed of information.

One place where this worldview of seeing everything as information leads is the reduction of reality to numbers, binary ones and zeroes – every last single bit of it.

If we look at the word in this way, we begin to see how it might feel more complex; because information is a discrete material thing that is undoubtedly becoming exponentially more voluminous every single second of every day.

Sometimes I feel utterly overwhelmed by the experience (or information) that pours into my senses at what feels like a totally unprecedented rate.

This flow sometimes feels like a huge filthy sewer leading directly into my mind as I am drawn in by the hypnotic allure of television or my mental defences are overrun by huge, gleaming over-sexualised street advertisements.

More often though, it feels far more morally neutral; like a sparkling fountain or stream of information that just never stops flowing, albeit one who’s flow is constantly increasing, as if a mighty storm were raging further up the valley.

I think this means that, as conscious, rational, present beings living in the world today, as we are increasingly seeing reality as a flow of information; we are finding it harder and harder to put the pieces together and form narratives about what’s happening in the world around us.

Our minds constantly grasp at the tools of culture that have developed and grown over millennia to try and find ways to simplify the frighteningly enormous volume of information that flows our way.

We want nothing more than to talk to like-minded people, to friends, to neighbours, to mentors, about the films and books and places and news items we have jointly experienced so that our minds can anchor onto something solid, something unmoving, something constant. We reminisce about the days when we would all watch the same TV program and then share our thoughts about it the next day at work or school. Now we each have a near-infinite choice of programs waiting for us on Netflix when we finish work each night and the chances of us having watched the same one so that we can discuss it with our colleagues the next day is becoming increasingly thin.

Increasingly, people are ditching the broadcast news as well as newspapers. More and more people are getting their news from the near infinite feeds (and therefore infinite potential narratives) of social media.

For many, a weekly religious gathering that once allowed people to come together in each other’s company and hear the same story (however dubious you might feel about the content of that story), simply no longer exists in their lives at all.

The core narratives that we all agree upon so that we can move forward with a shared sense of purpose are vital and are beginning to be lost.

The gradual mechanisation and digitisation of more and more areas of our lives over the last couple of centuries has slowly led to our minds adopting a new way of seeing, one that increasingly reshapes our perception to match the machines, computers, robots and algorithms that we see in the world; a mechanistic way of seeing.

We often don’t even realise it but the way that we think about how things work, in society, our work, our homes, politics and business has become more and more systematised, more mechanical.

The way we explain to ourselves how things fit together and interact with each other was once organic, messy, a bit chaotic, which left open the possibility of radical change. Now we explain things through machine-like analogies because machines are penetrating our cultural sub-strata to a level that is not only unprecedented but is also increasing at an exponential rate.

Soon almost everything we have created will be controlled by some sort of mechanical or digital mechanism, from all of the tools we use to communicate to the vehicles we use to travel around. The methods we use to pay for every single thing we buy; the ways we produce, store, prepare and cook all of our food; the medical care we provide will all soon either become completely automated or at least attached to or controlled by a machine or computer of some kind.

As a consequence, we increasingly think of cause and effect solely in the reductionist terms of machine thinking. Democracy works like a machine: grinding on under its own steam, churning out decisions and legislation, even though it is totally in the hands of people, in their diversity, richness and infinite beauty.

Our distribution and logistical systems – how we move and distribute all of the things we need to survive – are seen as well oiled machines, efficient and increasingly automated.

Each and every business is now seen as a giant machine that must at all costs be driven forward by the sole motive of efficiency, fooling ourselves into thinking we are taking its control out of the hands of people with all of their complexities, nuances, messiness and unreliability.

We now increasingly even think of our brains simply as super-complex computers, calculating their energy use and calculation rate as if they were manufactured in Silicon Valley.

In the midst of all the confusion arising all around the world as a result of the perceived increase in complexity, some people in positions of power have chosen to take advantage of this confusion as well as the new way in which we see the world and use mechanised and highly-automated tools of distraction to keep our attention firmly centred on shiny, attractive and hypnotising things that can be placed in front of our face to keep us under control while in the background they dismantle the structures of civilisation in order to attain insatiable amounts of power and wealth.

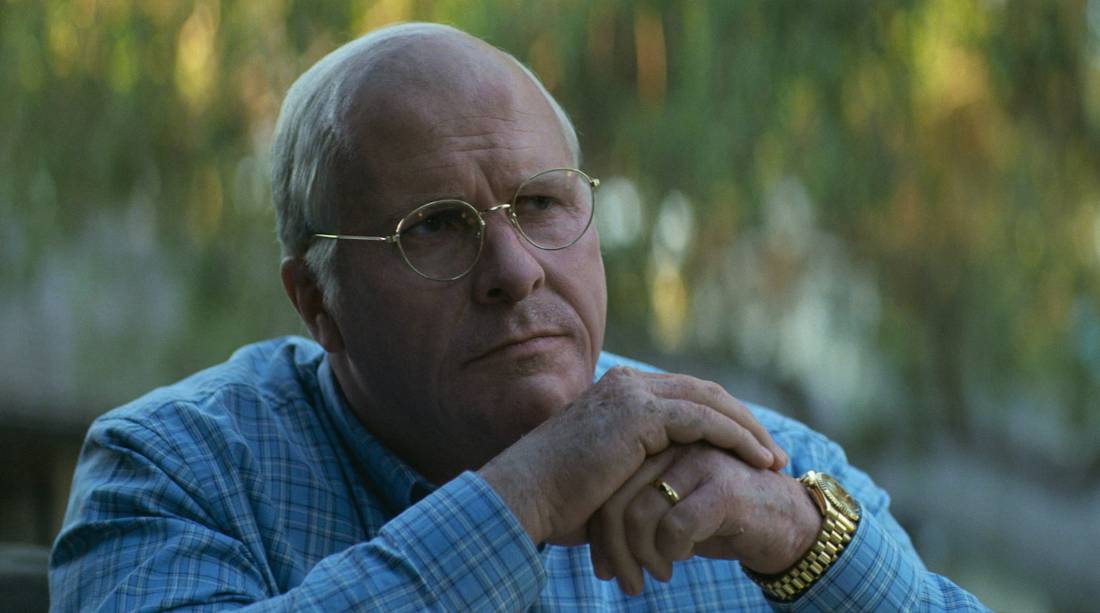

Vice, the latest film by Adam McKay, details how Dick Cheney is undoubtedly one of these people and probably one of the most successful in recent history at pulling off this trick. While Vice-President of the USA between 2001 and 2009, he applied what he had learnt earlier from masters of deception and distraction such as Henry Kissinger in ways that are eerily similar to the actions of the master Russian trickster Vladislav Surkov. He unleashed untold physical and mental destruction on the world, funneled trillions of dollars into the pockets of his friends, acquaintances and fellow travellers, entirely abandoning his duty to confront the catastrophic contemporary problems of human civilisation such as climate change by wielding almost unlimited amounts of executive power.

In order to get away with all of this in the middle of an apparently democratic state with a free press, multi-branch government structure and highly literate citizenry, the film demonstrates how Cheney applied the skills that he had learnt from fly-fishing to make people look exactly where he wanted them to; directly away from his shady shenanigans.

He, like many fishermen before him, knew that if you distract the fish with the right lure, you can make them do absolutely anything. If you construct the lure out of the right material, you can burrow right down into the fish’s natural instinct and trick it into surrendering itself completely; thereby giving itself entirely over to the whims of the fisherman.

This works for humans just the same as it does for fish, you just need to construct your lure out of television, Netflix, video games, shopping centres, alcohol, drugs, food, or sex instead of maggots and feathers.

In other words, vices are not just myriad harmful traps that we as individuals can accidentally fall into, but are also lures that people with power and no morals craftily encourage, promote and facilitate in order to keep us distracted and prevent us from reaching our full potential while they steal and hoard the world’s resources for themselves.

The deliberate destruction of the structures of civilisation by Governments and shady hangers-on in recent years has helped to enable the reemergence of a dark side of the human psyche that many, maybe somewhat naively, had forgotten still remained alive and kicking; fascism.

Except the fascism that we now see all around the world creeping once more out of the deep, dark burrow that many thought it had been consigned is different to the strain that we have seen before.

This time, to dovetail into the culture of our era, it has evolved to leach off a technological host.

Increasingly, people worship material technology while promoting their misguided belief that everything in the universe is simply made from cold, hard atoms.

Technology is the messiah. Numbers are king. Science is God. All Hail! And down with anyone who believes in any wishy-washy social woo-woo nonsense like Art or the study of the ‘humanities’. Everything must be measured and anything that can’t be measured either does not exist or doesn’t matter. The logical endpoint of this ideology is painfully obvious; total nihilism.

When we believe the only thing that exists is the material, any space for something greater, more mysterious or even different evaporates. What then grows in those mental furrows is something very dark indeed.

In today’s world, that darkness is growing.

The problem for men like Dick “heartless” Cheney, the place where their clever little plan comes unstuck, is that the accumulation of power and wealth do not – and ultimately will never – go unnoticed.

Part of the reason for this is that you can’t erase knowledge. If you do something evil, the overwhelming likelihood is that somebody somewhere will have seen you do it and therefore that person has ‘knowledge’ of your evildoing. Now that knowledge, once in existence, is sticky, it hangs around and is almost impossible to erase if you are the evildoer. Sure, knowledge can be forgotten, but that usually takes generations and rarely happens to truly important knowledge. The only other real way to erase knowledge if you are an evildoer is to kill all of those with the knowledge but obviously this then creates yet more knowledge of evildoing and so on ad infinitum.

These men try to hide their loot and attempt to draw a curtain around their power-play but these actions always have wildly unpredictable and chaotic consequences that literally nobody, not even the most powerful supercomputers with their most advanced models, can predict. What this increasing chaos looks like to the outsider is an exponential increase on the ‘crazy-scale’; they can’t figure out why person X is committing actions Y and Z but they sense intuitively that these actions just don’t make sense in a sane, rational world.

Just take a look around you at the kind of things that have been happening over the last few years, the bizarre, ever-more-extreme craziness that is piling up day-by-day. The world, which once felt understandable and within our grasp, today seems increasingly weird and unexplainable.

In this milieu, many develop conspiracy theories in an attempt explain the craziness that they see around them.

The techno-fascists attempt to explain the craziness in the only way that they can (if all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail); using a technological metaphor. They nonchalantly assert that we live inside a simulation controlled by some higher martian cyberlord.

Humans are and always will be exceptionally curious problem-solvers, and therefore our natural reaction to the confusion caused by an elevation of the ‘crazy-scale’ is to double down and try even harder to put the puzzle pieces back together-to try and understand what on earth is going on.

This means that for the lords of darkness to remain hidden behind the curtain, the power of the distraction machine must increase.

However an increase in sensory stimulation for the purposes of distraction can only lead to one inevitable outcome: over-stimulation. People simply can’t take any more. Sure, they’re distracted from the reality of what’s happening around them, but there’s only so much vice we can take. Eventually we will get bored of Netflix, the drugs we take will stop having the effect they once did, the bad food we eat will lose its taste and ability to satisfy us, the things we buy to make us happy will stop doing so, we will begin to crave more than base carnal pleasure.

Our minds and bodies are clever, more than it’s ever possible to know, and will eventually realise that something is not quite right, that things are out of balance and, setting out on the path to re-correct the balance, they will learn to become aware again. Then it’s only a matter of time before the energy currently consumed by vice is once again available to start putting the puzzle pieces back together again.

We do not live inside a machine or a simulation and the natural state of (wo)man is not to seek power or wealth or pleasure, or even happiness; it is to be present and open to the Truth of experience, to learn, grow and day-by-day slowly become a better, more conscious person.