A brilliant video essay explaining how the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image animée works, providing a sustainable funding model for French moving image culture, as well as helping to push Film forward as a radical, constantly evolving art form.

Tag: film

January means the annual appearance of David Ehrlich’s latest Best Films of the Year video.

Yes, it’s a simplistic purified distillation, a click-baity listicle at heart, a confection engineered to mine short-term cinephilic nostalgia – and yet these days, nothing rekindles my love for the incredible art form of Cinema, nothing reminds me what’s so magic about those 24 simple frames per second as much as David Ehrlich’s yearly treat.

The true magic, the actual Art, lies within the films themselves of course. However this doesn’t detract from the fact that Ehrlich is a master-editor who is able to make the best films of the year riff off each other to wonderful, emotive effect. He finds ways to draw out topical themes, strands of deeper meaning within the collective arc of the year’s artistic output, elevating their individual genius to an even greater teritory.

Pacifiction (2022, dir. Albert Serra)

Cows and Peasants

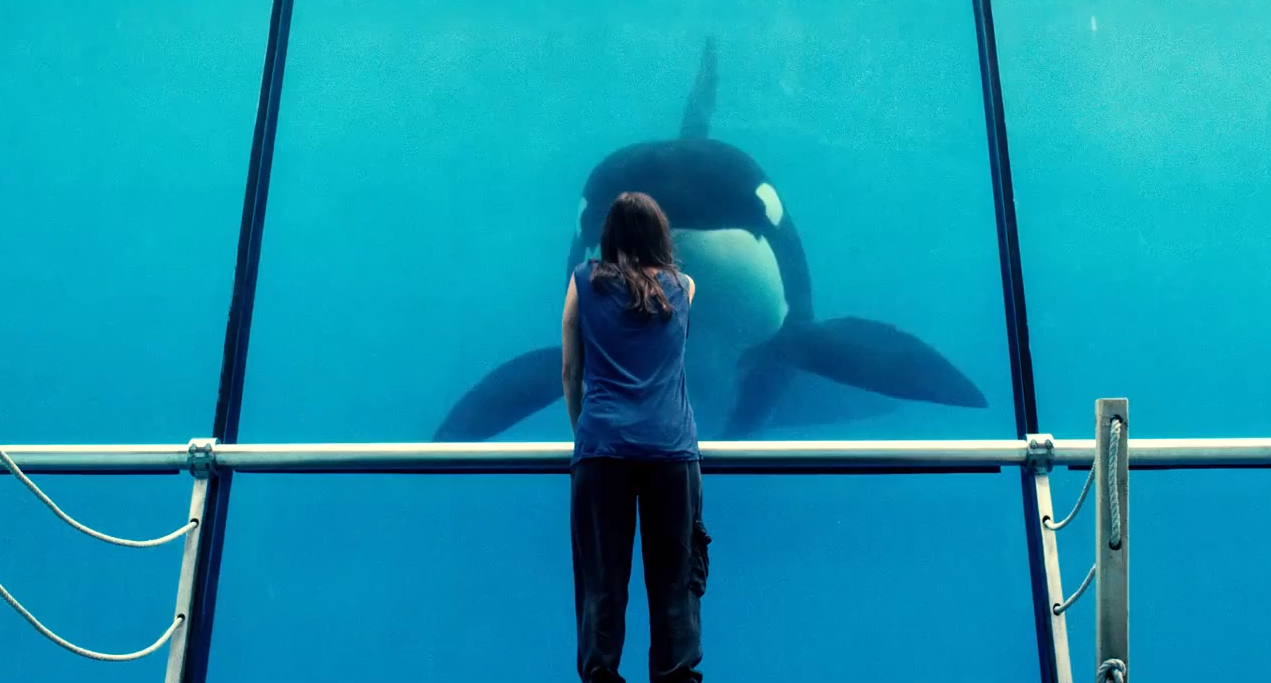

Andrea Arnold’s documentary Cow presents the life of a dairy cow as sad, hard and painful as a result of the way she is exploited for her milk, daily, for almost her entire life.

Although never doing so explicitly, the film suggests implicitly that, because of this painful exploitation, the very practice of dairy farming, one that has been carried out in almost every part of the world for millennia, should probably stop.

It’s hard to argue with this view.

The reality of a dairy farm, as presented by Arnold over the course of her 90 minute film, is pretty grim. We see newborn calves in distress as they are removed from their mother’s side, cows forced into pens to be unceremoniously impregnated by bulls and the indignity of older cows being forced onto wooden blocks in the milking parlour so that the farm-hand can fit the milking machinery onto their sagging udders.

I have a sneaking suspicion that the particular dairy farm presented in the film is a particularly humane example of those that span the globe.

But might there be more to the story of dairy farming than the apparent cruelty on display here?

John Berger would have thought so.

In his own doc, Pig Earth, based on the novel of the same name, which is in turn inspired by his years living in a farming village in the French Alps, Berger talks about what it means to be a peasant at a time when mass mechanisation is radically reshaping agriculture and pushing vast numbers of peasants off the land and into cities.

Berger notes that at that time (the late 1970’s), most of the world’s humans are peasants, working their little patch of the Earth for their whole life. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of all the humans that have ever lived throughout recorded history were also peasants.

This is a startling fact that shouldn’t be dismissed and perhaps ought to be considered carefully by anyone who wishes to hand down judgements on what particular types of agriculture we should or shouldn’t be practicing.

But Berger goes further.

He argues that peasant culture is a highly evolved, complex, nuanced form of society that has developed over thousands of years to work in symbiosis with nature to overcome the immense challenges of feeding human civilisation in a holistic, natural and sustainable way.

He proposes that the mechanised, bio-tech led agro-business that is increasingly displacing peasants in the process of providing food for people can never do what peasant culture has been doing effectively for thousands of years now due to the inherent contradictions in its process and relation to nature.

Throughout Pig Earth, Berger provides lived, first-hand experience of the intelligence, wit, cunning, indefatigability and philosophy of peasants who work the land.

He suggests that cows are as much a part of peasant culture – and by extension our broader global culture due to peasants providing much of our food supply – as houses, fields and rivers. It is all one holistic system that has been operating in symbiosis with nature for thousands of years.

There is a moment in Pig Earth where Berger states that all of the work that a peasant family does in the fields over the 365 days of a year is purely to feed the family and their cows. Every single bit of it.

Of course, things have changed sightly since the 1970’s, but not as much as we might think. The vast majority of the world’s food is still produced by farmers who’s parents, grandparents and great-grandparents all worked the land – people who Berger would think of as peasants.

As we head into a future of less biodiversity, soil erosion, water shortages, constraints on resources like fertilisers and potentially a lack of energy to power things like machinery and agricultural equipment, the skills embedded in peasant culture, passed down through the generations will be needed more than ever.

Perhaps we should think a little more deeply before being so quick to dismiss dairy farming and all that it supports, as presented in a documentary like Cow.

The American Friend somehow manages to coalesce the inner psychological turmoil of the main character – a German maker of picture-frames recently given a terminal diagnosis – with the gritty urban landscape of 1970’s Hamburg and other cities.

It’s hard to think of a film that so effectively marries the inner mind with the the outer urban environment in such a tight way as Wim Wenders achieves here.

Both the inner and outer worlds depicted in the film seem to be decaying, falling apart at the seams. The problem for Jonathan and the family he supports however, is that decaying cities can be regenerated, whereas decaying bodies – not so much.

There’s much more to this story than terminal decay however. Wenders is a filmmaker inherently aware of the power of spirit and that’s hardly more apparent than in this beautiful piece of work, where he endows the light in every scene with a spiritual majesty that helps to reinforce the fact that there is always a little more to reality than material decay.

P.S. thanks for introducing me to the Old Elbe Tunnel which is cute A.F.

Life can be hard. It can grind you down as the years roll on by. But it’s by trying to find the light amidst the darkness that allows us to keep going despite all that bears down on us.

The light can take many forms; the stability of a tightly-bound community; the passion of a loving romance; the spiritual pull of great music; an afternoon on an empty beach; the transcendent beauty of the way Roger Deakins captures the subtle hope in melancholic morning sunlight. All these things and many more can send our hearts aflutter and furnish us with the spirit to push on. Whatever works. Just find the light.

Over-Stimulation in the Distraction Machine

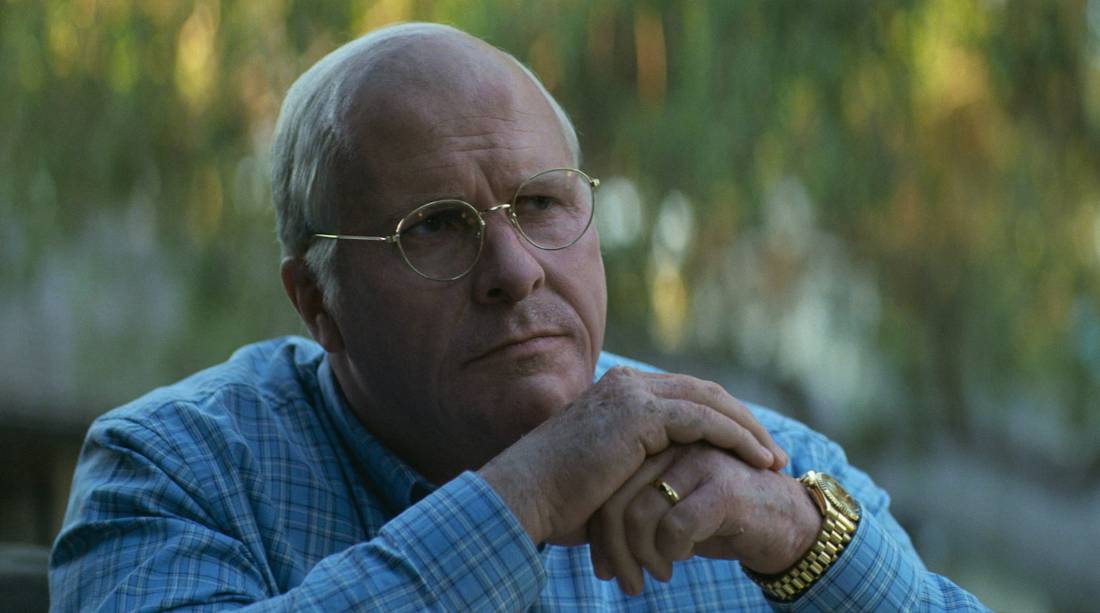

A Rumination on Adam McKay’s Vice

”Beware of the quiet man. For while others speak, he watches. And while others act, he plans. And when they finally rest……he strikes.” – Anon

It feels like the world is becoming more complex.

So what’s causing this new complexity?

Well, there do seem to be more ideas floating around today. Everyone’s mind is working overtime churning out opinions and thoughts, and with more people in the world now than at any time in history, it’s enticing to adopt the logic that all those new thoughts (in the form of Tweets, articles, books, interviews and conversations) are making society more complex. But maybe most of these ideas and opinions are simply recycled, reused and remixed from older ones? Indeed, originality is a hard concept to pin down, but it seems to me that little of what flows out of us today can be labelled truly original.

So what about technology? It does feel like all the new technology that we are inventing is producing more complexity in society, for sure. But crucially, I feel our technological inventions of the past century have led to a new and radically different way of seeing the world; one where the things in the natural world begin to look and feel like the technology we are inventing.

Once we begin interacting with computers more than people; everything in reality starts to feel like it is constructed of information.

One place where this worldview of seeing everything as information leads is the reduction of reality to numbers, binary ones and zeroes – every last single bit of it.

If we look at the word in this way, we begin to see how it might feel more complex; because information is a discrete material thing that is undoubtedly becoming exponentially more voluminous every single second of every day.

Sometimes I feel utterly overwhelmed by the experience (or information) that pours into my senses at what feels like a totally unprecedented rate.

This flow sometimes feels like a huge filthy sewer leading directly into my mind as I am drawn in by the hypnotic allure of television or my mental defences are overrun by huge, gleaming over-sexualised street advertisements.

More often though, it feels far more morally neutral; like a sparkling fountain or stream of information that just never stops flowing, albeit one who’s flow is constantly increasing, as if a mighty storm were raging further up the valley.

I think this means that, as conscious, rational, present beings living in the world today, as we are increasingly seeing reality as a flow of information; we are finding it harder and harder to put the pieces together and form narratives about what’s happening in the world around us.

Our minds constantly grasp at the tools of culture that have developed and grown over millennia to try and find ways to simplify the frighteningly enormous volume of information that flows our way.

We want nothing more than to talk to like-minded people, to friends, to neighbours, to mentors, about the films and books and places and news items we have jointly experienced so that our minds can anchor onto something solid, something unmoving, something constant. We reminisce about the days when we would all watch the same TV program and then share our thoughts about it the next day at work or school. Now we each have a near-infinite choice of programs waiting for us on Netflix when we finish work each night and the chances of us having watched the same one so that we can discuss it with our colleagues the next day is becoming increasingly thin.

Increasingly, people are ditching the broadcast news as well as newspapers. More and more people are getting their news from the near infinite feeds (and therefore infinite potential narratives) of social media.

For many, a weekly religious gathering that once allowed people to come together in each other’s company and hear the same story (however dubious you might feel about the content of that story), simply no longer exists in their lives at all.

The core narratives that we all agree upon so that we can move forward with a shared sense of purpose are vital and are beginning to be lost.

The gradual mechanisation and digitisation of more and more areas of our lives over the last couple of centuries has slowly led to our minds adopting a new way of seeing, one that increasingly reshapes our perception to match the machines, computers, robots and algorithms that we see in the world; a mechanistic way of seeing.

We often don’t even realise it but the way that we think about how things work, in society, our work, our homes, politics and business has become more and more systematised, more mechanical.

The way we explain to ourselves how things fit together and interact with each other was once organic, messy, a bit chaotic, which left open the possibility of radical change. Now we explain things through machine-like analogies because machines are penetrating our cultural sub-strata to a level that is not only unprecedented but is also increasing at an exponential rate.

Soon almost everything we have created will be controlled by some sort of mechanical or digital mechanism, from all of the tools we use to communicate to the vehicles we use to travel around. The methods we use to pay for every single thing we buy; the ways we produce, store, prepare and cook all of our food; the medical care we provide will all soon either become completely automated or at least attached to or controlled by a machine or computer of some kind.

As a consequence, we increasingly think of cause and effect solely in the reductionist terms of machine thinking. Democracy works like a machine: grinding on under its own steam, churning out decisions and legislation, even though it is totally in the hands of people, in their diversity, richness and infinite beauty.

Our distribution and logistical systems – how we move and distribute all of the things we need to survive – are seen as well oiled machines, efficient and increasingly automated.

Each and every business is now seen as a giant machine that must at all costs be driven forward by the sole motive of efficiency, fooling ourselves into thinking we are taking its control out of the hands of people with all of their complexities, nuances, messiness and unreliability.

We now increasingly even think of our brains simply as super-complex computers, calculating their energy use and calculation rate as if they were manufactured in Silicon Valley.

In the midst of all the confusion arising all around the world as a result of the perceived increase in complexity, some people in positions of power have chosen to take advantage of this confusion as well as the new way in which we see the world and use mechanised and highly-automated tools of distraction to keep our attention firmly centred on shiny, attractive and hypnotising things that can be placed in front of our face to keep us under control while in the background they dismantle the structures of civilisation in order to attain insatiable amounts of power and wealth.

Vice, the latest film by Adam McKay, details how Dick Cheney is undoubtedly one of these people and probably one of the most successful in recent history at pulling off this trick. While Vice-President of the USA between 2001 and 2009, he applied what he had learnt earlier from masters of deception and distraction such as Henry Kissinger in ways that are eerily similar to the actions of the master Russian trickster Vladislav Surkov. He unleashed untold physical and mental destruction on the world, funneled trillions of dollars into the pockets of his friends, acquaintances and fellow travellers, entirely abandoning his duty to confront the catastrophic contemporary problems of human civilisation such as climate change by wielding almost unlimited amounts of executive power.

In order to get away with all of this in the middle of an apparently democratic state with a free press, multi-branch government structure and highly literate citizenry, the film demonstrates how Cheney applied the skills that he had learnt from fly-fishing to make people look exactly where he wanted them to; directly away from his shady shenanigans.

He, like many fishermen before him, knew that if you distract the fish with the right lure, you can make them do absolutely anything. If you construct the lure out of the right material, you can burrow right down into the fish’s natural instinct and trick it into surrendering itself completely; thereby giving itself entirely over to the whims of the fisherman.

This works for humans just the same as it does for fish, you just need to construct your lure out of television, Netflix, video games, shopping centres, alcohol, drugs, food, or sex instead of maggots and feathers.

In other words, vices are not just myriad harmful traps that we as individuals can accidentally fall into, but are also lures that people with power and no morals craftily encourage, promote and facilitate in order to keep us distracted and prevent us from reaching our full potential while they steal and hoard the world’s resources for themselves.

The deliberate destruction of the structures of civilisation by Governments and shady hangers-on in recent years has helped to enable the reemergence of a dark side of the human psyche that many, maybe somewhat naively, had forgotten still remained alive and kicking; fascism.

Except the fascism that we now see all around the world creeping once more out of the deep, dark burrow that many thought it had been consigned is different to the strain that we have seen before.

This time, to dovetail into the culture of our era, it has evolved to leach off a technological host.

Increasingly, people worship material technology while promoting their misguided belief that everything in the universe is simply made from cold, hard atoms.

Technology is the messiah. Numbers are king. Science is God. All Hail! And down with anyone who believes in any wishy-washy social woo-woo nonsense like Art or the study of the ‘humanities’. Everything must be measured and anything that can’t be measured either does not exist or doesn’t matter. The logical endpoint of this ideology is painfully obvious; total nihilism.

When we believe the only thing that exists is the material, any space for something greater, more mysterious or even different evaporates. What then grows in those mental furrows is something very dark indeed.

In today’s world, that darkness is growing.

The problem for men like Dick “heartless” Cheney, the place where their clever little plan comes unstuck, is that the accumulation of power and wealth do not – and ultimately will never – go unnoticed.

Part of the reason for this is that you can’t erase knowledge. If you do something evil, the overwhelming likelihood is that somebody somewhere will have seen you do it and therefore that person has ‘knowledge’ of your evildoing. Now that knowledge, once in existence, is sticky, it hangs around and is almost impossible to erase if you are the evildoer. Sure, knowledge can be forgotten, but that usually takes generations and rarely happens to truly important knowledge. The only other real way to erase knowledge if you are an evildoer is to kill all of those with the knowledge but obviously this then creates yet more knowledge of evildoing and so on ad infinitum.

These men try to hide their loot and attempt to draw a curtain around their power-play but these actions always have wildly unpredictable and chaotic consequences that literally nobody, not even the most powerful supercomputers with their most advanced models, can predict. What this increasing chaos looks like to the outsider is an exponential increase on the ‘crazy-scale’; they can’t figure out why person X is committing actions Y and Z but they sense intuitively that these actions just don’t make sense in a sane, rational world.

Just take a look around you at the kind of things that have been happening over the last few years, the bizarre, ever-more-extreme craziness that is piling up day-by-day. The world, which once felt understandable and within our grasp, today seems increasingly weird and unexplainable.

In this milieu, many develop conspiracy theories in an attempt explain the craziness that they see around them.

The techno-fascists attempt to explain the craziness in the only way that they can (if all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail); using a technological metaphor. They nonchalantly assert that we live inside a simulation controlled by some higher martian cyberlord.

Humans are and always will be exceptionally curious problem-solvers, and therefore our natural reaction to the confusion caused by an elevation of the ‘crazy-scale’ is to double down and try even harder to put the puzzle pieces back together-to try and understand what on earth is going on.

This means that for the lords of darkness to remain hidden behind the curtain, the power of the distraction machine must increase.

However an increase in sensory stimulation for the purposes of distraction can only lead to one inevitable outcome: over-stimulation. People simply can’t take any more. Sure, they’re distracted from the reality of what’s happening around them, but there’s only so much vice we can take. Eventually we will get bored of Netflix, the drugs we take will stop having the effect they once did, the bad food we eat will lose its taste and ability to satisfy us, the things we buy to make us happy will stop doing so, we will begin to crave more than base carnal pleasure.

Our minds and bodies are clever, more than it’s ever possible to know, and will eventually realise that something is not quite right, that things are out of balance and, setting out on the path to re-correct the balance, they will learn to become aware again. Then it’s only a matter of time before the energy currently consumed by vice is once again available to start putting the puzzle pieces back together again.

We do not live inside a machine or a simulation and the natural state of (wo)man is not to seek power or wealth or pleasure, or even happiness; it is to be present and open to the Truth of experience, to learn, grow and day-by-day slowly become a better, more conscious person.

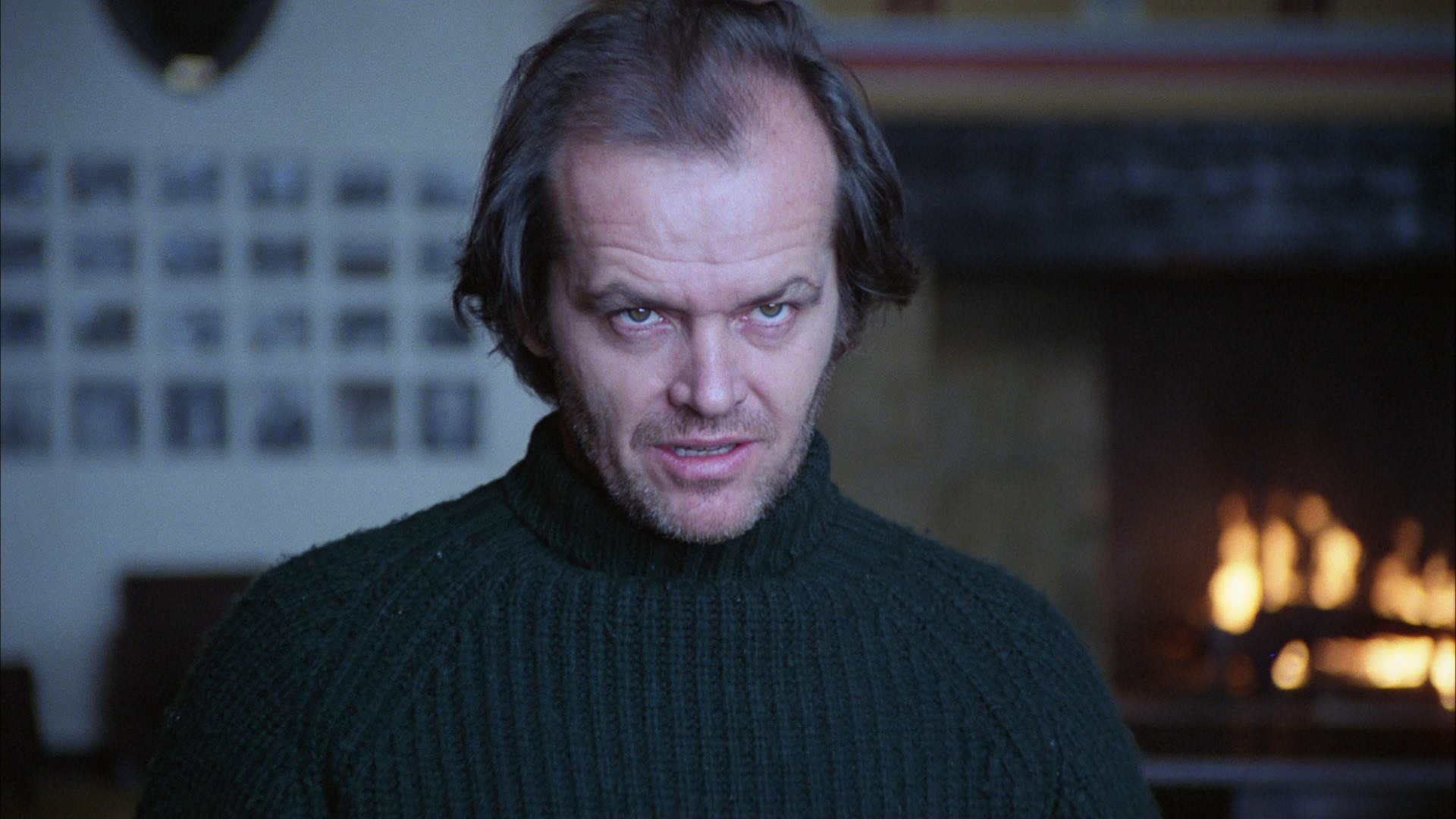

Why The Shining is the Best Horror Film Ever Made

“He wanted to make a ghost film. A ghost film! You know, just that – a good ghost film [that was] scary. That’s what he wanted to do.”

Holy Motors and the Wonder of Cinema

The average film is made up of over 150,000 individual images or “frames” displayed one after the other at high speed. If it is projected using 35mm film, a shutter will momentarily close between each frame, preventing any light from leaving the projector while the frame changes. This means that if you’re watching a film projected in 35mm, for half the film you are sat in complete darkness!

Top 20 Films of 2012

This may get said every year, but 2012 was a truly great year for film. With new films from Malick, Mendes, Tarantino, the Wachowskis and Paul Thomas Anderson, it was extremely difficult to make this list. 2012 was an especially good year for documentaries too with a handful that had some really interesting things to say.

Before we move on to the actual list, an honourable mention goes to; Liberal Arts, Arbitrage, The Sessions, Sightseers, Ginger & Rosa, Les Miserables, Marley, Shadows of Liberty, McCullin, Moonrise Kingdom, On The Road, Frankenweenie, End of Watch, Babeldom and Canned Dreams.

20. Chronicle

Chronicle caught me off guard. Released in the fifth week of the year, it was hidden amongst a cluster of Oscar contenders and initially looked as if it might be another Skyline. It turned out to be quite the opposite. The film takes a unique look at the possession of super-powers and has some very impressive special effects to boot. All-in-all, Chronicle is an extremely original film that builds until the action-packed finale.

19. Lore

The indoctrination of children with Nazi ideals by their SS parents is a subject many film makers would find hard to approach. Not Cate Shortland however. In Lore, she has crafted a beautiful yet poignant coming-of-age film that tackles some extremely interesting ideas. Set at the end of WWII, the atmosphere throughout is dark and at times close to apocalyptic. The film contains a huge amount of humanity however which only adds to its emotional strength.

18. The Cabin in the Woods

Joss Whedon was probably best known in 2012 for his super-budget blockbuster Avengers but far superior in my opinion is his much smaller film The Cabin in the Woods. The less you know about the storyline, the better but I will say that the story – like Chronicle – is highly original and contains a healthy dose of satire.

17. Searching for Sugar Man

This is the story of how Rodriguez, a 70’s singer-songwriter from Detroit, failed to gain fame and fortune in his native country and spent his life living in poverty while simultaneously, unbeknown to him, selling millions of records in South Africa and Australia. The film tells the story with great energy and enthusiasm and is without doubt one of the best documentaries of the year.

16. The Imposter

Like one of those Channel 4 documentaries that seem to simply be a platform for exhibiting freaks on prime-time television, The Imposter draws you in by its premise alone. The film tells the true story of a 23 year old French man who claims to be the missing 16 year old son of a Texas family. It is a prime example of truth being stranger than fiction and will have you on the edge of your seat from start to finish.

15. The Impossible

Telling the true story of a family caught in the middle of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, The Impossible is both deeply harrowing and immensely up lifting. The film achieves a sense of realism that few modern films can equal by ditching the special effects in favour of a giant water tank.

14. Ruby Sparks

Ruby Sparks is another film that caught me off guard. At first it seems like your average rom-com but as it goes along, it begins to get darker and a lot more interesting. By the end it has posed some pretty interesting questions and will definitely be getting a re-watch from me.

13. The House I Live In

If The Wire isn’t enough to convince you that the War on Drugs has failed, this hugely insightful documentary by Eugene Jarecki will definitely do the job. By interviewing everybody from addicts to police officers, politicians to judges, Jarecki puts forward a cohesive argument that will leave all but the most authoritarian lawmakers questioning their previously held views on drugs.

12. Skyfall

As soon as I heard that Sam Mendes was taking the reins of the 23rd Bond film, my ears pricked up. When it was announced that Javier Bardem was starring as the villain, I got excited. Skyfall doesn’t disappoint. By stripping it down and building a solid, character-driven story from the ground up, Mendes has perhaps created the best Bond film since Goldfinger. It’s gritty, sincere and most important of all, extremely well acted. Bond purists and newcomers alike will not be disappointed by this fantastic addition to the series.

11. Beasts of the Southern Wild

I have no idea how this low budget indie flick got a mainstream release but boy am I glad it did. The fact that Quvenzhané Wallis was only five years old when she played the leading role only adds to the fact that this is one of the best stories to appear in 2012. The enchantment and pure thirst for life that flows from each frame of this film is a true sight to behold.

10. To the Wonder

Terrence Malick is a genius. That much is undisputed. Every single one of his films are simply dripping with his thirst and curiosity for life. There are many however that feel his more recent work has become slightly pretentious and meaningless. I wholeheartedly disagree. To the Wonder is not only a beautiful and mesmerising work of art, it also explores deep and complex ideas that few filmmakers are brave enough to touch.

9. Amour

Amour is an extremely touching film about love, growing old and one of the World’s greatest taboos: death. At times it is difficult to watch due to its sheer emotional gravitas but ultimately it is a triumph of cinematic realism that draws you right into the hearts of the characters involved.

8. Rust and Bone

Marion Cotillard and Matthias Schoenaerts give two incredible performances in this gritty but beautifully told story. From start to finish it is somewhat of an emotional roller coaster ride, taking you from the lowest of lows to the highest of highs and proves that French cinema is in better health than ever.

7. Django Unchained

While not as good as some of his past work, Tarantino’s latest is still miles ahead of most other films. The script is fantastic and Tarantino manages to somehow tease yet another outstanding performance from Christoph Waltz. While the subtext of the film is not as ground breaking as some claim, it still raises some important points about slavery and civil rights. Whatever you may say about Tarantino, he is still one of the best writers in Hollywood today.

6. Silver Linings Playbook

Our society literally has no idea what to do with those who suffer from a “mental illness”. It is almost considered taboo sometimes and rarely gets talked about as openly and with as little stigma attached as it should. Silver Linings Playbook tries its hardest to correct this. On the surface, it can be seen as a simple rom-com but there is so much more to it than that. It is a beautiful character study of two people who both struggle to live their lives because of the mental illness from which they suffer. The thing that really draws me to the film however is, as Brett Easton Ellis put it: “Silver Linings Playbook grabs the audience by the lapels and shrieks Feel! Feel! Feel!”. In a World overwhelmed with mediocrity and an increasing lack of emotion, we need more films like Silver Linings Playbook.

5. Life of Pi

Life of Pi is a beautiful philosophy-rich film which is not only unafraid to ask big questions but does so with style, panache and sincerity. I’m sure much of this is owed to the original novel but Ang Lee still does a marvellous job of bringing this so called “un-filmable” book to the screen. The special effects are truly groundbreaking and likewise the cinematography is simply stunning, with a beautifully vibrant colour palate. As a family friendly hollywood film that leaves you not only with a smile but ideas to contemplate at the end, this is hard to beat.

4. Samsara

Like Baraka and Koyaanisqatsi before it, Samsara is a work of genius. I won’t say too much about it as I have already written an extensive piece about it here. I will say however that the art of film making doesn’t get much better than this and although it may be a bit too unorthodox for some people, if you let it simply wash over you, you may be pleasantly surprised.

3. Killing Them Softly

Killing Them Softly has to be the most criminally underrated film of 2012. On the most basic level, it is a fantastic noir thriller set around the criminal fraternity of a decaying American city. The film reaches much deeper than this however and intelligently juxtaposes the 2008 economic collapse with the collapse of the local criminal economy. The acting is top draw with Brad Pitt, Ben Mendelsohn and Scoot McNairy all delivering fantastic performances and the choice of music is also brilliant.

2. Cloud Atlas

In any other year, Cloud Atlas would be number one on this list. It is a very special film and I believe its true artistic value will only be realised in the years to come. It is impossible to describe the plot due to its sheer complexity, spanning 6 story lines in 6 completely different time periods from 1849 to the 24th century. I don’t think I have ever seen a film that has so much intellectual ambition while still presenting it in a format that is easily accessible. I still need to watch it again before saying anymore about it as there is so much that I missed the first time around but if there’s one film you see in the near future, make this it.

1. The Master

Paul Thomas Anderson is arguably the greatest living film director and The Master shows exactly why this is the case. From start to finish, it’s an absolute film making masterclass. PTA has some magical ability to squeeze the performance of their career from his leading actors and this is never more evident that in this film with Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman both giving performances better than any other in 2012. It is simply criminal that neither won an Oscar. The acting is only a small part of what makes this film a masterpiece however. The script, including the subject matter covered is truly fantastic but we have almost come to expect this from PTA these days. The cinematography is some of the most beautiful this year, shot entirely on 70mm film which makes it almost pop off the screen. I also had high expectations for Johnny Greenwood’s score which certainly didn’t disappoint. All in all, The Master is in a league of its own and I can’t see a film this decade coming anywhere near it, let alone this year.